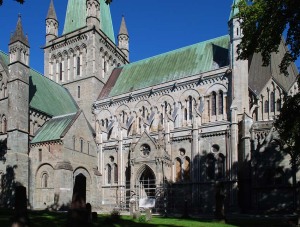

The south side of Nidaros Cathedral (Trondheim, Norway) - the northernmost medieval cathedral in Europe. It is mainly built from soft metamorphic stone like soapstone and greenschist.

Stone to the northernmost of Europe’s great cathedrals was provided from no less than 50 different quarries across Norway and to some extent from elsewhere in Europe. But there are great differences between the medieval building period (11th to 14th century) and the time of large-scale restoration and reconstruction from the late 19th century onwards These differences reflect cultural change – in traditions, technology, fashion – and is a main theme in a new project I’m working on.

The Trondheim region is not blessed with easily workable “European” building stone like sandstone and limestone, so in the Middle Ages metamorphic stone like soapstone, greenschist, marble and gneiss were provided from local and regional quarries, generally close to the sea since transport by boat must have been essential. Quarrying evolved at places where small-scale exploitation of soapstone pots and other items had previously taken place. Thus, at least three major quarry centres (at Øysanden, in Trondheim and in Sparbu) emerged – and they also provided stone for other churches and monasteries in the region. Since the art of stone building was only introduced with Christianity in the 10-11th century, foreign, especially English, stone workers were quite certainly involved in the development of quarrying.

There are lots of fascinating stories on stone that can be inferred from the medieval building archaeology and the archaeology of the quarries. For example, the first stone that was imported to Norway in the Middle Ages was a superb black marble gravestone from Belgium (c. 1160). For one reason or another it later ended up as a roofing stone in the central tower of the cathedral! And the use of white marble columns as a contrast to the otherwise greyish and blue-green stones in the facades must have been inspired by the popularity of the famous Purbeck marble, though in England dark Purbeck was used as a contrast to otherwise light-coloured building stones. The cathedral even had a Purbeck “sister quarry”; a dolomite marble deposit spectacularly located at a little island (Allmenningen) off the rugged coast some 140 km north of Trondheim.

The marble quarry at Allmenningen island, 140 km north of Trondheim, provided stone for Nidaros Catheral both in the Middle Ages and during the restoration that started in 1869.

Fires, political circumstances and poor maintenance implied that the cathedral was a half-ruin as restoration and reconstruction started in 1869. Few stone buildings had been erected in Norway after the Middle Ages and as quarrying was taken up again it was carried out more or less as in the Middle Ages. However, black powder and new railroads (and later better roads) eased extraction and transport; thus deposits farther away from Trondheim and, notably, away from the coast could be taken in use. There was a formidable run for good soapstone and exploration across the country was carried out with the aid of the Geological Survey of Norway. In addition, famous stone, such as marble from Fauske, was applied.

As the cathedral is now being “re-restored” there is again a big need for good stone. The Restoration Workshop is constantly on the search for especially soapstone, but at the moment the delivery situation is pretty unclear.

I have worked with the cathedral’s stone for more than 20 years and time has come to collect the material into a popular scientific book. There will be overviews and stories on quarries and quarrying through history. Work and life in the quarry centres, especially in in Central Norway, will be a focal point, but a main question will also be: Why does soapstone, Norway’s “national stone” seem to be so important? From a technical and geological point of view there would have been other, perhaps better, options – options that may not have been fashionable enough or not founded on existing traditions.

The project, called “The Stones of Nidaros – life and work in the cathedral’s quarries through 1000 years” is supported by the Restoration Workshop of Nidaros Cathedral and The Norwegian Non-fiction Writers and Translators Association. Also, work on the project is aided by the Geological Survey of Norway. The book will be published in Norwegian (hopefully by 2012), but an extended English abstract as well as a Google Maps application is planned, which may be of interest for foreign readers.

Further reading

Storemyr, P., Lundberg, N. Østerås, B. & Heldal, T. (2010): Arkeologien til Nidarosdomens middelaldersteinbrudd. In: Bjørlykke, K., Ekroll, Ø. & Syrstad Gran, B. (eds.): Nidarosdomen – ny forskning på gammel kirke. Trondheim: Nidaros Domkirkes Restaureringsarbeiders forlag, 238-267. [The archaeology of Nidaros cathedral’s medieval quarries] Download PDF (2,8 MB)

Storemyr, P. (2003): Stein til kvader og dekor i Trøndelags middelalderkirker. Geologi, europeisk innflytelse og tradisjoner. In: Imsen, S. (ed.): Ecclesia Nidrosensis. Søkelys på Nidaroskirkens og Nidarosprovinsens historie. Trondheim: Tapir Akademisk Forlag, 445-463 (with English abstract). [Stone for ashlar and decoration at Central Norwegian medieval churches: Geology, European influence and traditions] Further information.

Storemyr, P., Degryse, P. & King, J.F. (2007): A black Tournai “marble” tombslab from Belgium imported to Trondheim (Norway) in the 12th century: Provenance determination based on geological, stylistic and historical evidence. Materials Characterization, 58, 1104-1118. Abstract and further information

Storemyr, P. (1997): The Stones of Nidaros. An Applied Weathering Study of Europe’s Northernmost Medieval Cathedral. Ph.d-thesis, no. 1997:92, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim. Download PDF (19,1 MB)

Hello- is it possible some of the soapstone used in Nidaros Cathedral came from (the island of ) Svanøybukt ?

I have been told by residents whose families have lived on the island for generations that there was a soapstone quarry there which was used in the construction of St. Mary Cathedral in Bergen. Thank you

Probably not. To far away. But, yes, the quarry was used in Bergen, but maybe not as far back as in the Middle Ages (St. Mary’s Chrurch). It was used for portals (etc.?) at Nykirken in the 18th Century. And probably for regional works on the far west coast further back (Kinn church). All best, Per

Pingback: Good stone doesn’t change its location! | Per Storemyr Archaeology & Conservation

Pingback: Of Rocks and Whiskey « GeologyWriter.com – Writing by David B. Williams

Pingback: Miscellanea | www.businessstone.com

Pingback: Miscelânea | www.businessstone.com